NBBS: Well, welcome to the NBBS podcast. I’m Lewis Hassell, our host today, and I’m pleased to introduce to our listeners Dr. Joan Walker. Dr. Walker is a professor of gynecological oncology at the University of Oklahoma. She’s a noted national and international expert on the topics of gynecological cancer with a particular interest in cervical cancer. Indeed, as we were talking beforehand, she said no person should have to die of this disease. So, I think that gives you an orientation about her philosophy and personality. Welcome to the NBBS podcast, Dr. Walker.

Dr. Walker: Well, thank you, I’m glad to be here.

NBBS: I wonder if first off, we could talk a little bit about how big a problem cervical cancer is in the world.

Dr. Walker: It is. It’s the number one killer of women, unfortunately a completely preventable disease and yet 400,000 get cervical cancer every year, and the United States is no better, just like COVID. We have about 12 to 14,000 people get cervical cancer and 4000 die, and completely preventable and absolutely irresponsible.

NBBS: Well, you know, it seems that sometimes, at least in the United States and I suspect internationally, that different populations are affected differently. What’s the reason behind the variations between ethnic socioeconomic groups and so forth with regard to this disease?

Dr. Walker: Well, again, just like COVID, vaccinate, vaccinate, vaccinate. We everybody between 9 and 45 is eligible to be vaccinated for HPV. And the optimum age is prior to puberty. So, between 9 and 12 is ideal. The vaccine is expensive. Probably $1000 to do all three vaccines. In Viet Nam, it’s about 4 million dong for 3 shots. If you are vaccinated really young, you don’t need three shots. It works better when you’re young. And it’s a little controversial as to how many you need, just like COVID. But right now, older folks need three shots, but younger folks only need 2.

There’s more than one vaccine, but generally speaking, we’re using Gardasil, which is a 9 valent HPV vaccine. And we have a clinical trial that we’re doing here in Oklahoma where all of our cervix cancer patients are becoming vaccine advocates. There is an anti VAX movement in the United States, and I don’t know maybe worldwide now since the COVID vaccine has brought that out. And a lot of mothers are afraid to get their kids vaccinated for, unfortunately, misinformation reasons. Therefore, we’re trying to have every cervix cancer patient and everybody who’s been affected by HPV (vulvar cancer, tonsillar cancer, or anal cancer). Doesn’t matter what kind of cancer, we’re trying to educate them with a video and trying to have them become advocates to communicate to their communities.

In the US, it’s a rural population problem. It’s also a problem secondary to tubal ligation that women are really good about getting their Paps done when they get birth control pills. And they can’t get their pills prescription filled unless they get their Paps done. And so we tend to have control over the screening for cervical cancer during childbearing years. And then if they get contraception, such as tubal ligation and don’t have a need to get their prescription filled, they tend to disappear and never show up to a doctor’s office again.

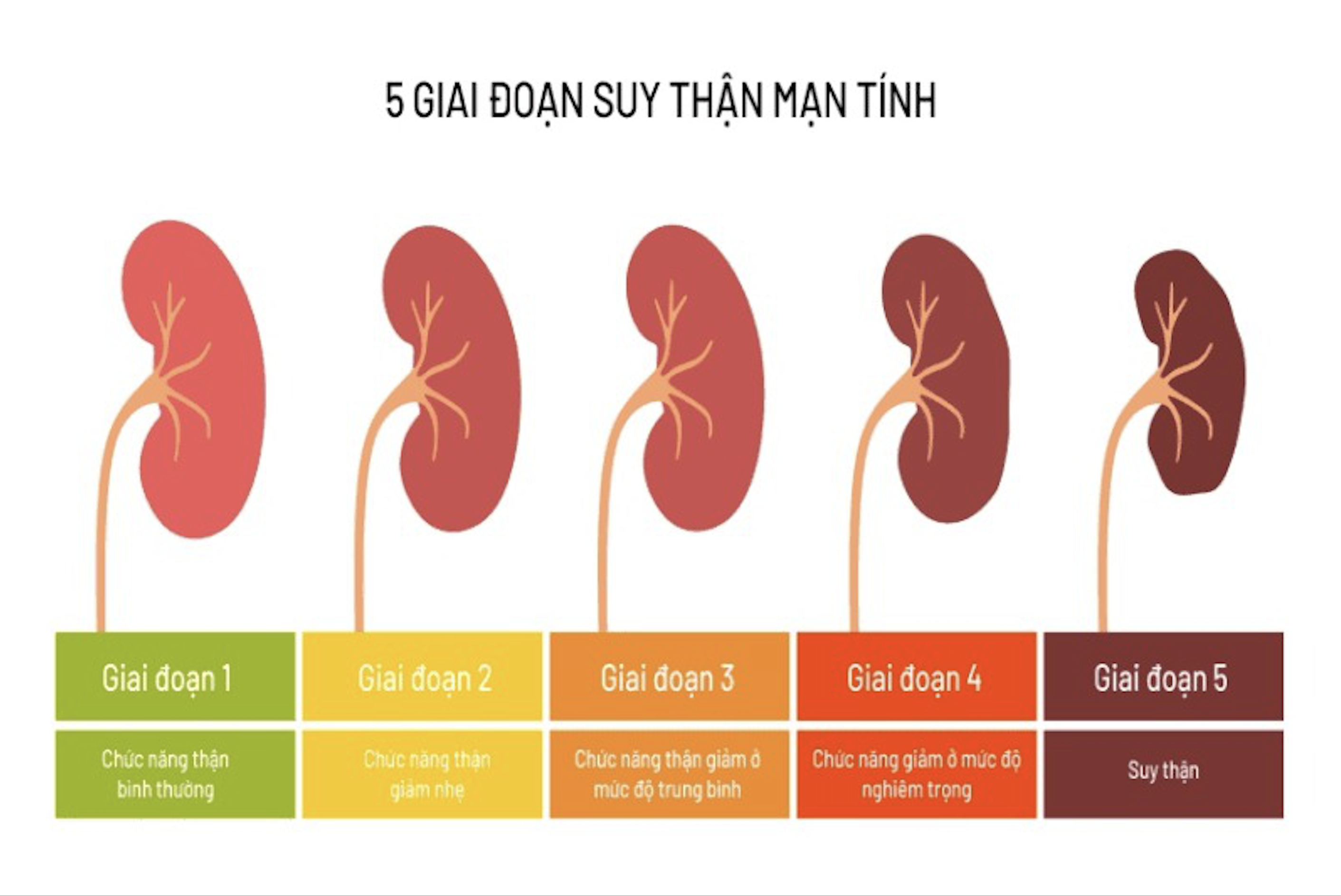

And people who are infertile, people who are obese, people who are menopausal, and people who had their sterilization procedures, tend to get cervical cancer just because of the lack of health care. We have kind of a belief here that if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it in Oklahoma. And I am sure that’s kind of the same problem in Africa and India and Southeast Asia. You know you only go to a doctor if you have a problem and so unfortunately, people don’t come in until they’re bleeding to death or have renal failure or some major problem.

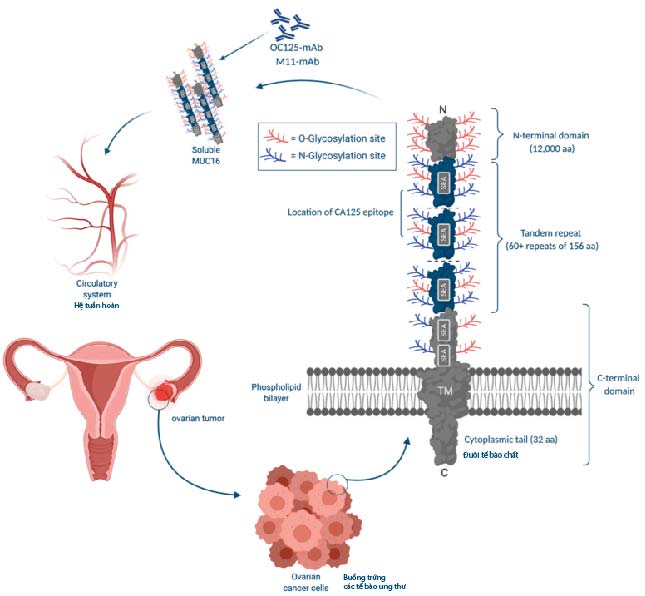

NBBS: I think that’s a very important point to recognize that in order to prevent this disease, there has to be preventive services and preventive examination and so forth. But let’s just go back just to make sure that our listeners understand the very direct connection between the human papilloma virus (HPV) and this disease as well as the other cancers that you’ve mentioned. How does that happen? When does the infection occur? How does it promote the development of cancer and what’s the kind of the time course of that?

Dr. Walker: Yes, that’s a good point. I wish I could show my slides. I have a natural history slide which shows you that people tend to have sex about age 15 or 16 in the United States. I’m not really educated about sexual onset in different populations. But we have to vaccinate against HPV before menarche in order to avoid having people get infected with the first intercourse. A lot of our patients get cervical cancer in the US because they didn’t get vaccinated until they realized they needed it, and that was usually after they’re sexually active and then it’s too late. And so, mothers tend to protect their children from sexual thought processes and education until they think they need it. And if you wait till they’re 16 or 17, it’s too late. They’re already having contact. So my wishes is we start at 9. Hopefully if you keep trying to get the kids vaccinated starting at age 9, maybe by age 12, you’ve gotten it done. It really needs to be done by age 12. And access to vaccinations hopefully will get improve in other countries. Now that COVID has been so well advertised and the social justice of our country providing vaccines to other countries has been well demonstrated with COVID. I hope that will wake up to the recognition that if we vaccinated the whole world, we’d all be better off. And providing those vaccines at cost or cheaper is really mandatory. Having Merck licensed their vaccination patent to other countries like we’re doing with COVID, getting it manufactured worldwide and getting Africa and India and Southeast Asia to rev that up would really be remarkable. So hopefully COVID is going to be a good thing. Hopefully, it’s going to teach us to take better care of the world. And maybe cervix cancer will go away. But I said the exact same thing when HIV happened. I thought: “Oh well, everybody’s going to wear condoms. And no, there’s not going to be any cervix cancer anymore, because people will be afraid of promiscuous sex and stuff.” And that was absolutely false.

NBBS: So how safe is the HPV vaccine? You mentioned there’s three dose courses and so forth, and then also you mentioned that some adult older women are eligible for the vaccine. So, talk about some of the decision points in that regard.

Dr. Walker: Well, you’re supposed to get it before you’re 12 as I said, and that is ideal. We have been giving it free.

It is helpful – I would say – to have HPV be a cause of other kinds of cancers besides cervix cancer. The fact that it’s a cause of tonsillar cancer. And there’s been famous people who have gotten tonsillar cancer and made it well known that it’s HPV related may help us to just call it a cancer vaccine rather than a vaccine for sexually transmitted diseases. Having it be an anti-cancer vaccine may make mothers more willing to give it at age 9-12. There are people who have had a monogamist relationship, let’s say until the death of their partner, or to have or the divorce or whatever. Those people do choose to get vaccinated at an older age. So let’s say a 30-year-old loses her husband for whatever reason. She may choose to be vaccinated when she didn’t get the vaccine when she was a child in order for her to have a new partner and not be afraid of getting cancer. So, there are there are people who choose to be vaccinated older and there is a federal law that protects physicians and the pharmaceutical company from lawsuits if a vaccine complication does occur. And so it’s always good to follow the label and make sure that the vaccination is given for the proper indications; and it used to be that it was only indicated for 9- to 18-year-old, and then it was up to 26 and now it’s up to 45. So you can safely vaccinate people between those age groups for whatever reason: the patient feels it is indicated or the doctor feels it is indicated. And usually, it’s some kind of a change in sexual partner.

NBBS: We’ve talked a little bit about screening and PAP testing and some places they’re doing HPV testing in lieu of pap testing and so forth. How frequently should people be screened in today’s world and maybe in countries where you know there’s not a robust screening program, what would you recommend that they go for?

Dr. Walker: Well, there is an interesting phenomenon in Japan. So, it can’t be generalized to all countries. In Japan, there are HPV negative adenocarcinomas. They’re more common in Asian people than they are in the US. So I would still recommend PAP screening in Asia because they do have this propensity and you don’t want to screen for a cancer and miss some patients who are compliant and then fail to get seen for the right disease is just horrible. In the United States we do HPV plus PAP. That has been done for quite some time now and it’s very effective and every five years is fine when you have a double negative. The thought process is you can go to HPV alone because HPV is a much more sensitive test than a PAP and it also doesn’t give you the uncomfortable reading of ASCUS, or LSIL, or HSIL and not know what’s going on. But when you have a positive HPV, the doctor still needs the PAP to know what to do with it. And it seems like we ought to be reflexing backwards, so we ought to do the HPV. If it’s negative, you don’t need to do the Paps. But if it’s positive, you do. Because you still need to know what to do next. And so, HPV test alone is believed to be more cost effective, but it is awkward for us to deal with as gynecologists. So, I have to just admit that. In the world, probably the most efficacious thing to do is HPV test alone. But again, Asia is special, and I’m not sure about every other country. And we don’t have enough data.

We did do a clinical trial of AGUS/AGC kind of patients, atypical glandular cells, or we enrolled patients with AGC PAP tests and did their HPV typing and evaluated them and we found we were missing these Asian women. And so, we have not done that in every country, and I can’t comment on where else we might be making mistakes.

NBBS: Yeah, so there’s still a fair bit to learn about some of these nuances and the other regards. So even though with a vaccine, we’re going to need to continue to screen for this disease if we want to preserve families and …

Dr. Walker: Well, I don’t know the answer to that cause the prevalence will start to be very small. And so cost effectiveness and all those silly tests you know, still probably have to be figured out after vaccination. But the most important thing, at least in the US, is people vaccinate too late. So they can think they’re vaccinated, but they can’t stop screening because they …. If they’re honest with themselves, they know they’ve had contact prior to the vaccine in way too many times, and so we are currently doing the double screen every five years with a PAP plus HPV to be the most conscientious even in the vaccinated population.

NBBS: And just to sort of reiterate, when you mentioned the time of first contact in 15-17, in that age range, the times when the cancers start to appear as a result of those contacts are quite usually about 10-15 years later?

Dr Walker: Yeah, you know the average age of abnormal Paps is about 35. However, you know I’ve had 21 year olds die of cervix cancer.

NBBS: Yeah, so it can be very fast?

Dr Walker: There isn’t right. There isn’t a hard and fast rule. My usual thought processes are you get cervical cancer first or cervical dysplasia first; you get vulvar cancer second. That’s usually a little bit older, maybe 10 years older. So, we often see vulvar cancer 10 years after the cervical dysplasia. And then tonsillar and anal are usually in the 50s 60s. So, they’re a lot later, but we fill our clinics in 25- to 35-year-old range with our dysplasia clinics and then our cervix cancers in the United States -the average age is about 42. And the older folks are more likely to die than the younger folks. Because the younger folks are typically getting screened and getting birth control pills and having babies and so we catch him a little earlier. The patients who’ve had their tubes tide and haven’t been seen in a doctor’s office for more than 10 years tend to come in with stage 3B disease, then renal failure, where the creatinine is 10 and their hemoglobin is 6. And that’s what we usually see in Oklahoma, unfortunately.

NBBS: If all of our screening and preventive measures are unsuccessful, tell us a little bit about how you have to approach cervical cancer in terms of what patient symptoms bring them in and kind of what their treatment options become once they have established disease.

Dr. Walker: Well, ideally the patient is found to have cervical cancer because of an abnormal pap. And so ideally the patients come in and have a cervical biopsy, a colposcopy. You find the lesion, and you categorize the lesion. So, it’s either CIN 1, 2, or 3. It’s high grade or it’s low grade. And we tend to follow a lot of patients for HPV positive, who do not have high grade disease. Those who have high grade disease, high grade dysplasia usually gets a Leep or a Cone. And then they either have just dysplasia with negative margins and get followed again in six months with an HPV test. Or they have invasive cancer when we deal with what the diagnosis is. So, the diagnosis often is microinvasion or adenocarcinoma in situ or something that’s treatable with just a hysterectomy alone. And that’s ideal if it’s less than 3 mm or AIS. We can do a hysterectomy and cure the patient. We don’t even have to do oophorectomy or nodes.

Lymph vascular space invasion is a special circumstance where we have to be more worried about spread. Or if the lesion is 5 mm depth of invasion. Or a lesion that’s grossly visible one centimeter or two, then they get into another category which we call a 1B cervical cancer. The 1B cervical cancer is still only in the cervix, still curable and they have choices of radiation or surgery.

Younger patients tend to want surgery. They want to be cured without radiation, so they can preserve their ovarian function and their sexual function. And a radical hysterectomy is surgical treatment rather than a simple hysterectomy. We tend to get positive margins and high rate of recurrence with a regular hysterectomy. We have to do a radical hysterectomy removing the local tissue surrounding the cervix in order to be sure that it doesn’t come back right there in the vagina or the parametria.

And we do lymph node dissection. And we tend to do an open laparotomy procedure now because of a randomized trial that showed that laparoscopy and robotic surgery was worse. But we are repeating that study. We do have some concerns about the preoperative evaluation and the surgical techniques that we’re modifying, and so the robotic versus open laparotomy surgery will open next year as a randomized trial. And we are planning on enrolling here in Oklahoma and it may be worldwide. It was worldwide last year or last time, but we are trying to control. The patients will all get an MRI preoperatively. We want to know exactly how big the tumor is and make sure the PET scans don’t show any lymph node metastases, et cetera. And then the surgical technique will be videoed, and we’ll make sure all the surgeons are qualified. It will be more rigorous, and we hope that we’ll have a successful robotic radical hysterectomy in the future.

NBBS: That would be great. This is such a devastating disease, in an advanced stage, for woman and her family. And as you say, it’s a tragedy because it is such a preventable disease. And as you’ve illustrated in your comments, a lot of the challenge is more social rather than scientific in a lot of respects with regards to preventing this. You know, if you were to put on your sort of visionary hat to looking forward, with what we have now in terms of vaccine and progress, what do you hope and foresee for the future in dealing with this disease worldwide?

Dr. Walker: Well, I believe that we have to have the vaccines mandatory. They should be given before kids go to school. It should be just like measles, mumps, rubella. And if HPV vaccine was mandatory, it would be given, and you know it’s a communicable disease. Why do we not treat it like a communicable disease? If we don’t stop it, it’s going to continue to kill people. So it shouldn’t be special, just because it’s transmitted sexually doesn’t mean it should be treated differently. And so just like COVID, just like measles, mumps, rubella, we have to make our vaccines given appropriately at the right time before this transmission and get rid of these diseases.

NBBS: So it would be a nice summary to say, you know, get the prevention, get the screening so that we could catch it early if you have one of those disorders that falls through the cracks; so that we can avoid all of this: much more expensive and costly care and much more devastating consequences in terms of people lives.

Dr. Walker: Oh yeah, I mean it’s really hard to cure a stage 3B patient. When we have patients with nephrostomy tubes in their kidneys and chronic pain, they’re on narcotics and they die anyway. We give chemotherapy and radiation, we have cisplatin, Taxol, bevacizumab, Pembroke. And even with all these wonderful drugs and you know our survival’s getting longer and longer, 18 months is not good. 24 months is not good. They still die of their disease. So it’s absolutely tragic, completely preventable. And you’re right, it’s a social disease. It’s caused by neglect. And I get more and more angry when I see the patients seeing internists for the diabetes and hypertension, but not getting any screening. We are developing self-testing. And so, the HPV test will soon be available in the drugstore as a self-test. And that can be just inserted through the vagina and sent to the lab. For HPV testing, there’s a grant where companies are asked to compete for trying to develop the kit that you use for the self-test. And Roche, I think, is probably the leading company in the HPV testing arena, so it can be shipped to Roche or whichever company is going to be the cheapest on the block. And hopefully that will make it more worldwide available. And the foundations are also trying to supply worldwide access to HPV testing.

And then you get into the problem of is the treatment available? I remember when I was in Southern California, we had all these four Mexican women coming to Southern California to get treated for their cervix cancer because they couldn’t get treated in Mexico. So when you do have access to the screening, then it makes you in trouble because you don’t have the treatment. So, you’re damned if you do, and you’re damned if you don’t, I guess.

NBBS: Well, Doctor Walker, this has been a very fascinating discussion and I appreciate your time. Are there any final words or recommendations you want to summarize for our listeners?

Dr. Walker: I guess, just be advocates. I think that’s the most important thing is don’t let patients neglect their preventative care. Sometimes I blame the doctors. Sometimes I blame the patients. I blame the pediatricians who don’t get the vaccines into the patients because there’s nothing more helpful to getting vaccines into kids arms and having the pediatricians say it is needs to be done today. Doesn’t matter where they came in for a cold or a sprained ankle or what; you give them that vaccine today if they haven’t had it in the age group, they should be getting it. Everybody, both patients, and public health officials, and pediatricians, and primary care doctors all need to be advocates for routine preventative care.

NBBS: Well, thank you so much, Dr. Walker. This has been a delight to talk to you and I know our listeners appreciate that. And to our listeners, we certainly welcome comments and questions which we try to address going forward. And until next time, make good choices, be wise, and may you find abundant health. Thank you very much.